-

Faculty of Arts and HumanitiesDean's Office, Faculty of Arts and HumanitiesJakobi 2, r 116-121 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of History and ArchaeologyJakobi 2 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Estonian and General LinguisticsJakobi 2, IV korrus 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Philosophy and SemioticsJakobi 2, III korrus, ruumid 302-337 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Cultural ResearchÜlikooli 16 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Foreign Languages and CulturesLossi 3 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of Theology and Religious StudiesÜlikooli 18 50090 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Viljandi Culture AcademyPosti 1 71004 Viljandi linn, Viljandimaa EST0Professors emeritus, Faculty of Arts and Humanities0Associate Professors emeritus, Faculty of Arts and Humanities0Faculty of Social SciencesDean's Office, Faculty of Social SciencesLossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of EducationJakobi 5 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Johan Skytte Institute of Political StudiesLossi 36, ruum 301 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of Economics and Business AdministrationNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of PsychologyNäituse 2 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of LawNäituse 20 - 324 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Social StudiesLossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Narva CollegeRaekoja plats 2 20307 Narva linn, Ida-Virumaa EST0Pärnu CollegeRingi 35 80012 Pärnu linn, Pärnu linn, Pärnumaa EST0Professors emeritus, Faculty of Social Sciences0associate Professors emeritus, Faculty of Social Sciences0Faculty of MedicineDean's Office, Faculty of MedicineRavila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Biomedicine and Translational MedicineBiomeedikum, Ravila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of PharmacyNooruse 1 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of DentistryL. Puusepa 1a 50406 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Clinical MedicineL. Puusepa 8 50406 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Family Medicine and Public HealthRavila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Sport Sciences and PhysiotherapyUjula 4 51008 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTprofessors emeritus, Faculty of Medicine0associate Professors emeritus, Faculty of Medicine0Faculty of Science and TechnologyDean's Office, Faculty of Science and TechnologyVanemuise 46 - 208 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Computer ScienceNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of GenomicsRiia 23b/2 51010 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTEstonian Marine Institute0Institute of PhysicsInstitute of ChemistryRavila 14a 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Mathematics and StatisticsNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Molecular and Cell BiologyRiia 23, 23b - 134 51010 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTTartu ObservatoryObservatooriumi 1 61602 Tõravere alevik, Nõo vald, Tartumaa EST0Institute of TechnologyNooruse 1 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Ecology and Earth SciencesJ. Liivi tn 2 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTprofessors emeritus, Faculty of Science and Technology0associate Professors emeritus, Faculty of Science and Technology0Area of Academic SecretaryHuman Resources OfficeUppsala 6, Lossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of Head of FinanceFinance Office0Area of Director of AdministrationInformation Technology Office0Administrative OfficeÜlikooli 17 (III korrus) 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Estates Office0Marketing and Communication OfficeÜlikooli 18, ruumid 102, 104, 209, 210 50090 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of Vice Rector for Academic AffairsOffice of Academic AffairsUniversity of Tartu Youth AcademyUppsala 10 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTStudent Union OfficeÜlikooli 18b 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Centre for Learning and TeachingArea of Vice Rector for ResearchUniversity of Tartu LibraryW. Struve 1 50091 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTGrant OfficeArea of Vice Rector for DevelopmentCentre for Entrepreneurship and InnovationNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0University of Tartu Natural History Museum and Botanical GardenVanemuise 46 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0International Cooperation and Protocol Office0University of Tartu MuseumLossi 25 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of RectorRector's Strategy OfficeInternal Audit Office

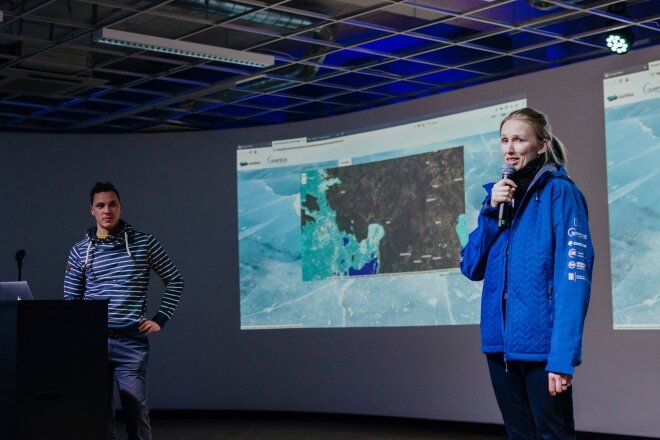

Team led by Junior Research Fellow of Tartu Observatory won the Copernicus OceanHack

The winners of Copernicus OceanHack are IceWise: the idea of creating an app to make moving on ice safe. The leader of the team was Junior Research Fellow of Tartu Observatory Kristi Uudeberg.

The goal of the hackathon was to create new applications by applying satellite data of the Baltic Sea. IceWise plans to combine Sentinel-1 data with ice thickness measurements made by citizens. Part of the app would be a map where layers with different data could be displayed on. For example, the map could show if there is any ice cover as well as the type of the ice. The satellite pictures of Sentinel-1 enable to assess that.

Besides that, the map would show the locations where people have measured ice thickness. The measurements would be of different reliability, which is why users would get to choose between seeing official measurements only, or adding the ones made by citizens as well.

Because there is little ice thickness measurement data, the measurements made by satellites are not reliable in our region. This is why the second part of the application would be data given by the users of the application. All of the users could enter ice thickness data of their measuring location, as well as warnings about different situations like ice cracks, openings, or thin ice. This kind of data would show on the map of the application and would be visible to everyone. "The more data like this there is, the more accurate the judgement of ice thickness derived from satellite data will be," Uudeberg stated.

Target group: from fishermen to ice yachters

The idea of IceWise was born this autumn at the Copernicus Roadshow event in Tallinn. At the masterclass, the creators of the National Weather Service's ice map stated that they were looking for a way to get information about ice thickness. "It turned out that there was no instrument to measure the thickness," Uudeberg said.

Actually, half of the team already met in September at the remote sensing autumn school organized by the University of Tartu for the first time. Uudeberg thinks that deep training schools like this, that bring young researchers and PhD students together, create good opportunities to meet different but yet like-minded people. By combining the experiences and skills of different people, the results can be very exciting. Uudeberg stated that she is very thankful to the BalticSatApps project that has helped her to attend events like this.

When the idea of IceWise had been accepted to OceanHack, Uudeberg started to look for people who would be interested in the measurements as well as do them themselves. The Estonian Environment Agency told her that ice thickness information was asked from fishermen who were more than happy to share it. Therefore Uudeberg asked fishermen what was important for them when going on ice, what was the data they took into consideration, and what were the data sources.

The more Uudeberg looked into the topic, the more communities seemed to be connected to it. This is how she also ended up talking to, for example, hike organizers, motocrossers, and ice yachters. "It turned out that there are quite a few measurements, but they are never forwarded to anywhere, they stay within the closed community," Uudeberg said.

Helpful atmosphere

Uudeberg, the leader of the winning team thinks that hackathons like OceanHack offer a great experience for everyone who is at least somewhat interested in the topic or want to put their skills or ability to perform under pressure to the test. At a hackathon, you work with strangers for a mutual goal for 48 hours straight. Uudeberg thinks that positive and supporting spirit as well as focusing on solutions are very helpful, because with a development process as active as this, a lot of things may not go as planned. "Plans B, C, D an even E have to be picked for a solution sometimes," Uudeberg said.

Among other things, at a hackathon one has to present their idea to other participants, mentors, and the judges within a very short time and be able to say everything necessary. Uudeberg thinks of this as a good exercise for similar situations outside the hackathon.

Among other things, at a hackathon one has to present their idea to other participants, mentors, and the judges within a very short time and be able to say everything necessary. Uudeberg thinks of this as a good exercise for similar situations outside the hackathon.

Hakathons also offer the opportunity to be advised by experts of the field. "A lot of knowledge is brought to you," Uudeberg stated. At OceanHack, mentors from around the world were there to give tips to the teams. Uudeberg thinks the mentors at hackathons are very helpful and create a supporting environment. "You feel taken care of and know that they hope you do well," she said.

Team IceWise was made up of six members: besides Uudeberg developers Karl Kruuse and Martin Laan, data scientists Age Arikas and Sander Rikka, and designer Anna Roomet.

Copernicus OceanHack was funded by the EU’s Copernicus Programme and organised through a partnership of EUMETSAT, the Copernicus Marine Environment Service, and the Estonian Environment Agency. The prize fund was 8000 euros.

More information: Kristi Uudeberg, Junior Research Fellow of Remote Sensing at Tartu Observatory, kristi.uudeberg [ät] ut.ee