University of Tartu 2024 wall calendar

University of Tartu 2024 wall calendar is based on the exhibition “Creativity2. University of Tartu researchers and art hobby” that was open from 21 June to 28 October 2023 in the University of Tartu Art Museum.

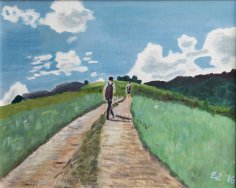

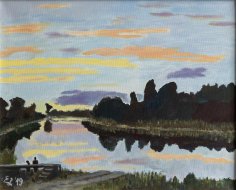

The exhibition brought together the members of the University of Tartu’s academic community, researchers with artistic hobbies for whom visual amateur art has, in various ways, served as an important output in addition to their research. The exhibition displayed the works of eight authors: Endla Lõhkivi, Ene Ustav, Imbi Traat, Inna Rebane, Jaak Kikas, Lemme Haldre, Tiina Kraav, Tõnu Esko. All of them have previously had solo exhibitions, but are together as scientists- artists for the first time.

Art has functioned in academic space in different ways over time, and in modern times, here and now, it seems to add the necessary positive energy and playfulness. Even the many exhibitions in the galleries of the university’s academic buildings confirm that.

The wall calendar was created with the help of the exhibition curators Ingrid Sahk and Maris Tuuling and graphic designer Maarja Roosi.

December – Tõnu Esko “3-D models of the Y-chromosome gene proteins” (2021)

Vice Rector for Development Tõnu Esko (1985) studied genetic engineering and received a doctorate in gene technology in 2012. Esko has worked at the University of Tartu since 2004, and his main fields of research are the study of the human genome, disease and behavioural genetics, and innovation transfer.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

The artist Markus Kasemaa has said, “Anything is art, but not every art must be pleasant or speak to the viewer”. The fact that I am a professor of human genomics has no influence on my perception of artistic creations. In art, I look for technical mastery I am unable to achieve myself.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

Art makes it possible to stress the important things – thoughts, phenomena, situations – anything irrelevant can be moved to the background or left out entirely. Artistic creation encourages one to think outside the box and clearly demonstrates how a topic can be approached in 1000 and 1 ways.

A favourite or role model in art

In art, I have the most fondness for the period from 1850–1950, impressionism to surrealism. However, any professional creation is intriguing. The biggest wow effect has come from futurism and the paintings by Umberto Boccioni – picturing movement in a static painting. There is a big chance of discovering something new every time one looks at museum-quality art – good art is deep and layered.

Professor emeritus Jaak Kikas (1949) studied physics and received a doctorate in physics in 1979. Kikas has worked at the University of Tartu since 1995, and his main fields of research are solid-state physics and optics.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

I wouldn’t like to determine art from such a narrow viewpoint. There is much in art that I can enjoy but cannot directly connect to my field of study in any way.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

A friend once asked whether I also make my pictures as a physicist. At first, I was confused, but thinking about it now, maybe these two fields truly have some common roots deep down. A chance to look at the world from a unique and unexpected angle?

A favourite or role model in art

As a solid-state physics researcher, I cannot pass by the wonderful works by Maurits Cornelis Escher that demonstrate various concepts in modern physics (symmetries, spatial transformations). However, as a photographer, I’m charmed by the compositions and magical garden views of Josef Sudek, the Czech master.

Lecturer in Mathematics Education Tiina Kraav (1981) studied mathematics and received a doctorate in mathematics in 2017. Kraav has worked at the University of Tartu since 2004, and her main fields of research are theoretical mechanics and mathematical education.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

Art is creation, in which I as a mathematician value order and structure maybe more than I would without such background. It is difficult to express a feeling that overcomes me when looking at a great piece of classic art, but I have experienced the same feeling also when reading a scientific paper. Creativity and creation do not always need a paintbrush to move the viewer or experiencer of the result. An elegant proof of a theorem is true art

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

The human brain can make itself visible in a number of ways. The visualisation of brain activity brought forth with our hands is immensely attractive to me. It’s a great honour to me to have some of that visualisation called art.

A favourite or role model in art

A favourite or role model in art? Marcel Wanders is a Dutch product designer and architect who, in my opinion, has most successfully blurred the distinction between art and design. Wanders is an artist who takes my breath away with his works.

Associate Professor Endla Lõhkivi (1962) studied chemistry and received a doctorate in philosophy in 2002. Lõhkivi has worked at the University of Tartu since 1986, and her main fields of research are philosophy of science, epistemology of science, scientific culture studies and philosophy of chemistry.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

For a science philosopher with a background in chemistry, art has a wide meaning, ranging from practical skills (art of cooking and dressmaking, debate or martial arts, even magic tricks or witchcraft) to fine arts like poetry and music, including visual arts. Chemistry used to be considered an art as well – even early 20th-century chemistry textbooks in Estonia defined chemistry as the art of combining and separating substances.

In the 18th century, when chemistry became the science we know it today, a Dutch scholar named Hermann Boerhaave declared in a public speech that chemistry is an art that becomes a science as it cleanses itself of impurities, doing it like a sculptor who forms perfect masterpieces of dirty raw materials, casting aside all the unclean and extraneous parts. Art certainly has that cleansing power.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

Perhaps doing art as a hobby is an attempt to realise unfulfilled childhood dreams. In the past, I didn’t even have a chance to try and see whether I could do it or not, even though I wanted to. I have been drawing for myself since early childhood. At some point, when reaching middle age, people suddenly have time for interests they had previously pushed aside; I have often noticed this among my peers. So, at the age of 54, I entered the Folk High School to learn the basics of painting. I certainly love paints and working with them, there is much to learn, and I certainly wish to continue. Naturally, at a slow pace, as a leisure activity.

A favourite or role model in art

When speaking only of painting, then I have always liked post-impressionists, like Cézanne, but also van Gogh, and Kandinsky’s Murnau period works. Tastes inevitably change, too; I have been liking abstract art more and more. No role models there. I’m still learning and painting mainly for myself.

Ene Ustav (1947) studied chemistry and received a doctorate in molecular biology in 1996. Ustav worked at the University of Tartu from 1975 to 2022, and her main fields of study are the research of the DNA replication mechanisms of the human papilloma virus (HPV) and the study of host/virus interactions.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

Delving into the mysteries of science arrived slightly later in life for me, in-between raising four children, but at the same time, understanding the life of the human papillomavirus has been so gripping and inspiring; there are so many interesting new hypotheses to check that it has been hard to stray from that path. An artist’s fantasy adds inspiration others may find hard to understand, of the “How do you come up with those things?” variety, but the proof of the truth is in the experiments!

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

The need for self-fulfilment and some inner urge to do something in the field of art has been looking for an outlet all my life. When I was studying chemistry at the university, I peeked into Kaljo Põllu’s art classroom that mainly focused on graphic works, tried to send works to Fine Arts Distance Learning Courses between taking care of the children and eventually made it to the Suvi studio.

A favourite or role model in art

The memories from my childhood, when the famous artist and art teacher Günther Reindorff and his wife spent several summers in Rõuge with my aunt, painting the familiar places I would go to pick wild strawberries. I remember the sense of pride when the famous artist gifted me an Italian charcoal pencil and a special soft eraser.

Associate Professor emeritus Imbi Traat (1950) studied mathematics, and received a doctorate in physics and mathematics in 1986. Traat has worked at the University of Tartu since 1974, and her main fields of research are mathematical statistics, multivariate statistics and sampling theory.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

For me, art entails beauty that engenders admiration and makes one feel good. A page of logical, mathematical text is also very beautiful. Expressing mathematics as simply as possible is beautiful. A feeling of understanding, fertile thought or discovery creates a sense of euphoria.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

The process of making a picture isn’t easy. It takes time. However, it feels good to like the final result.

A favourite or role model in art

I like Maris Tuuling’s paintings, her richness of colour, light and shadow, geometric style, dots and stripes.

Inna Rebane (1953) studied theoretical physics and received a doctorate in physics in 1981. Rebane worked at the University of Tartu from 1976 to 2020, and her main fields of research are theoretical issues of optical spectroscopy (spectroscopy of a single impurity molecule, spectral hole burning theory with light pulses, time-dependent theory of resonant secondary emission of impurity centres).

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

This question requires a deep (philosophical?) analysis. Many philosophers have certainly done so.

Solving theoretical physics questions or solving a cropped-up mathematics problem as well as painting have something in common – that is self-mobilisation and focusing all energy and attention on the thing one is solving or depicting. Ideas or solutions often pop up when I wake up in the morning. Creativity?

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

For self-expression. I loved drawing as a child. I learned how to paint at the Tartu Children’s Art School under Silvia Jõgever, and at the University of Tartu Open University under Anne Parmasto.

The process of painting is stressful, tiring, but also strongly therapeutic, distancing and releasing one from daily worries.

A favourite or role model in art

Vincent van Gogh

Lemme Haldre (1955) studied medicine and psychology and got the applied master’s degree in clinical psychology in 2002. She has worked at the University of Tartu as a lecturer, and her main field of work is as a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist (Elite Clinic, Tartu Children’s Support Centre).

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

What is art? I will have to pass on that answer. Many philosophical discussions and monographs have been published on the topic. The real truth isn’t there. Perhaps a modern artificial intelligence would say that only what it creates is art. I’ll leave it to every person to decide what art means to them.

I also use artistic means of expression in therapy with children, and sometimes even with adults. Many children, but also some adults prefer to express themselves non-verbally instead of speaking. An artistic metaphor helps people express emotions they don’t otherwise have words for.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

I have painted since I was a child, but the old hobby got pushed aside by work in the medical field. At some point in life, I felt I needed something additional to manage daily stress better. From that point on I found myself in the world of painting once more.

For me, painting is like a cleansing ritual, a form of meditation, one I cannot imagine a life without. While I paint, time and space seem to vanish; art is a chance to distance myself from the stresses of daily life, find an inner balance and recharge. I can then pass that energy onto my patients.

A favourite or role model in art

There are many. When naming just the first ones to come to mind, then Edvard Munch. If speaking of more modern ones, then Georg Baselitz. Out of deceased Estonian artists, Karl Pärsimägi, Peeter Mudist. There are also several modern Estonian artists whose works I enjoy.

Vice Rector for Development Tõnu Esko (1985) studied genetic engineering and received a doctorate in gene technology in 2012. Esko has worked at the University of Tartu since 2004, and his main fields of research are the study of the human genome, disease and behavioural genetics, and innovation transfer.

Tõnu Esko’s installation “Y-chromosome” is

- book “The Human Y-Chromosome”, print-out of 27 million nucleotide sequence, 5000 pages;

- DNA sequencing of the Y-chromosome as read out by the text-to-speech robot in the rhythm of the Bible’s sentence structure;

- 3-D models of the Y-chromosome gene proteins in a display case;

- Bibles on a shelf.

DNA or heredity material determines all properties of an organism – how it looks like, what it eats and where it lives, and what, or whether it thinks. DNA consists of four different nucleotides or base pairs – Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C) and Thymine (T).

A human DNA consists of 3.3 billion base pairs packed into 46 chromosomes, half of which are inherited from the mother and half from the father. When unravelled, a human DNA molecule would be almost 2.5 metres in length.

Still, how much information can be found in the DNA consisting of 3.3 billion base pairs? It may be suitable to have the Bible as a reference – it is a text that compiles the joys and suffering of being human, lays the baseline for societal norms and rules, and serves as a guide in times both good and bad.

An average Bible has about 1200 pages with approximately 3.1 million characters.

Therefore, it would take almost 1000 Bibles to write down a single human genome sequence.

A male’s Y-chromosome consists of 59 million base pairs, of which 27 million can be identified using modern sequencing technology. A Y-chromosome sequence would fit into eight Bibles.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

The artist Markus Kasemaa has said, “Anything is art, but not every art must be pleasant or speak to the viewer”. The fact that I am a professor of human genomics has no influence on my perception of artistic creations. In art, I look for technical mastery I am unable to achieve myself.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

Art makes it possible to stress the important things – thoughts, phenomena, situations – anything irrelevant can be moved to the background or left out entirely. Artistic creation encourages one to think outside the box and clearly demonstrates how a topic can be approached in 1000 and 1 ways.

A favourite or role model in art

In art, I have the most fondness for the period from 1850–1950, impressionism to surrealism. However, any professional creation is intriguing. The biggest wow effect has come from futurism and the paintings by Umberto Boccioni – picturing movement in a static painting. There is a big chance of discovering something new every time one looks at museum-quality art – good art is deep and layered.

Associate Professor Endla Lõhkivi (1962) studied chemistry and received a doctorate in philosophy in 2002. Lõhkivi has worked at the University of Tartu since 1986, and her main fields of research are philosophy of science, epistemology of science, scientific culture studies and philosophy of chemistry.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

For a science philosopher with a background in chemistry, art has a wide meaning, ranging from practical skills (art of cooking and dressmaking, debate or martial arts, even magic tricks or witchcraft) to fine arts like poetry and music, including visual arts. Chemistry used to be considered an art as well – even early 20th-century chemistry textbooks in Estonia defined chemistry as the art of combining and separating substances.

In the 18th century, when chemistry became the science we know it today, a Dutch scholar named Hermann Boerhaave declared in a public speech that chemistry is an art that becomes a science as it cleanses itself of impurities, doing it like a sculptor who forms perfect masterpieces of dirty raw materials, casting aside all the unclean and extraneous parts. Art certainly has that cleansing power.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

Perhaps doing art as a hobby is an attempt to realise unfulfilled childhood dreams. In the past, I didn’t even have a chance to try and see whether I could do it or not, even though I wanted to. I have been drawing for myself since early childhood. At some point, when reaching middle age, people suddenly have time for interests they had previously pushed aside; I have often noticed this among my peers. So, at the age of 54, I entered the Folk High School to learn the basics of painting. I certainly love paints and working with them, there is much to learn, and I certainly wish to continue. Naturally, at a slow pace, as a leisure activity.

A favourite or role model in art

When speaking only of painting, then I have always liked post-impressionists, like Cézanne, but also van Gogh, and Kandinsky’s Murnau period works. Tastes inevitably change, too; I have been liking abstract art more and more. No role models there. I’m still learning and painting mainly for myself.

Lecturer in Mathematics Education Tiina Kraav (1981) studied mathematics and received a doctorate in mathematics in 2017. Kraav has worked at the University of Tartu since 2004, and her main fields of research are theoretical mechanics and mathematical education.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

Art is creation, in which I as a mathematician value order and structure maybe more than I would without such background. It is difficult to express a feeling that overcomes me when looking at a great piece of classic art, but I have experienced the same feeling also when reading a scientific paper. Creativity and creation do not always need a paintbrush to move the viewer or experiencer of the result. An elegant proof of a theorem is true art

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

The human brain can make itself visible in a number of ways. The visualisation of brain activity brought forth with our hands is immensely attractive to me. It’s a great honour to me to have some of that visualisation called art.

A favourite or role model in art

A favourite or role model in art? Marcel Wanders is a Dutch product designer and architect who, in my opinion, has most successfully blurred the distinction between art and design. Wanders is an artist who takes my breath away with his works.

Associate Professor emeritus Imbi Traat (1950) studied mathematics, and received a doctorate in physics and mathematics in 1986. Traat has worked at the University of Tartu since 1974, and her main fields of research are mathematical statistics, multivariate statistics and sampling theory.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

For me, art entails beauty that engenders admiration and makes one feel good. A page of logical, mathematical text is also very beautiful. Expressing mathematics as simply as possible is beautiful. A feeling of understanding, fertile thought or discovery creates a sense of euphoria.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

The process of making a picture isn’t easy. It takes time. However, it feels good to like the final result.

A favourite or role model in art

I like Maris Tuuling’s paintings, her richness of colour, light and shadow, geometric style, dots and stripes.

Vice Rector for Development Tõnu Esko (1985) studied genetic engineering and received a doctorate in gene technology in 2012. Esko has worked at the University of Tartu since 2004, and his main fields of research are the study of the human genome, disease and behavioural genetics, and innovation transfer.

What is art (for a scientist, from the viewpoint of your field of study)?

The artist Markus Kasemaa has said, “Anything is art, but not every art must be pleasant or speak to the viewer”. The fact that I am a professor of human genomics has no influence on my perception of artistic creations. In art, I look for technical mastery I am unable to achieve myself.

Why do I need art or artistic hobbies?

Art makes it possible to stress the important things – thoughts, phenomena, situations – anything irrelevant can be moved to the background or left out entirely. Artistic creation encourages one to think outside the box and clearly demonstrates how a topic can be approached in 1000 and 1 ways.

A favourite or role model in art

In art, I have the most fondness for the period from 1850–1950, impressionism to surrealism. However, any professional creation is intriguing. The biggest wow effect has come from futurism and the paintings by Umberto Boccioni – picturing movement in a static painting. There is a big chance of discovering something new every time one looks at museum-quality art – good art is deep and layered.

Research done at the University of Tartu helps to meet sustainable development goals and solve societal challenges. The illustrations in the 2023 wall calendar reflect a selection of scientific topics through which the university and its researchers contribute to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Below, you can read more about the research projects included in the calendar.

The calendar aims to help raise awareness of the university's impact on solving global challenges and focus attention on the key issue of the recent and coming decades – sustainable development.

The author of the illustrations is Piret Räni, an artist and nature conservationist who has illustrated children's books and various information materials. She is passionate about environmental education and awareness and seeks to promote this through her creative work. In her illustrations for the calendar, the artist has combined classical ink drawing and visual simplification techniques.

The calendar has been printed on Nautilus® Classic recycled paper, bearing the EU Ecolabel.

January – “Reshaping Estonian energy, mobility and telecommunications systems on the verge of the Second Deep Transition”

The research group of Margit Keller and Laur Kanger is working on the project “Reshaping Estonian energy, mobility and telecommunications systems on the verge of the Second Deep Transition”. It aims to find ways to shape the development of the Estonian energy, transport and communications systems onto a sustainable and just path without repeating the past mistakes of industrial societies.

The way the Estonian energy and transport systems operate can be traced back to the experiences of Western industrial states in the interwar period. Currently, both systems produce large negative environmental impacts. Furthermore, the unequal distribution of these impacts in Estonia intensifies social inequality. In the Deep Transitions framework, the evolution of industrial societies is analysed through the interactions of socio-technical systems. The project brings together researchers from a wide range of disciplines – from social scientists to historians, linguists, innovation researchers and political scientists.

February – “E-governance and digital public services”

The project “E-governance and digital public services”, led by Mihkel Solvak, Associate Professor of Technology Research at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies, explores the potential of e-governance and the more efficient use of existing data, so that Estonia could be the first in the world to move to third-generation e-services that continuously take into account the experience of service users and predict their behaviour.

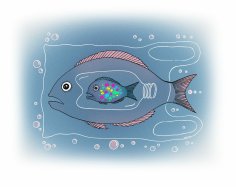

March – “Oceanic distribution of microplastics and the impact of such pressures on biota”

Jonne Kotta, Director of Research of the Estonian Marine Institute, leads the project “Oceanic distribution of microplastics and the impact of such pressures on biota”. A tenth of all plastic waste ends up in the oceans. Most of it breaks down into microplastics, which are difficult to detect with modern methods and technology. As there is currently no precise knowledge of the distribution of microplastics, the project aims to investigate the distribution of microplastics, including particles of less than 10 μm and various microfibres in water, sediments and biota from the coast to the deep ocean.

April – “Sustainable use of soil resources in the changing climate”

The research project of Leho Tedersoo, Professor in Mycorrhizal Studies of the Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, “Sustainable use of soil resources in the changing climate”, aims to study the impact of land use and climate change on the soil microbiome and carbon content and the emission of greenhouse gases from the soil. The project provides a good overview of greenhouse gas emissions and proposes environmentally sustainable solutions for the land-use change that is inevitable as a result of urbanisation and forestation of the tundra.

May – “Researching Europe, digitalisation, and conspiracy theories”

The work of Mari-Liis Madisson, Research Fellow in Semiotics of the Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics, “Researching Europe, digitalisation, and conspiracy theories”, helps to clarify the aims of conspiracy theories that divide society, explain how they spread and the impact they have on people. Understanding all of this will make it possible to better assess and prevent the dangers posed by the proliferation of conspiracy theories, to raise people's awareness and thus perhaps make them less vulnerable.

Mari-Liis Madisson's work contributes to the bridging of societal gaps and the early prevention of potential new gaps. It supports the development of a more cohesive society, both in Estonia and around the world, by increasing trust in public institutions and reducing society's vulnerability to crises.

June – “Inclusive sites and routes: shared stories and meaning-making”

The research project of Ülo Valk, Professor of Estonian and Comparative Folklore of the Institute of Cultural Research, “Inclusive sites and routes: shared stories and meaning-making”, focuses on places and routes with religious or mythical meaning, their increasing significance in modern society and the related processes.

The international working group focuses on initiatives specific to rural Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Norway, which revive forgotten but important places and create new destinations with an appeal that transcends social, ethnic and cultural boundaries. The project aims to understand why some of these places become truly inclusive while others cause antagonism and social tension.

July – International incubation programme of Viljandi Culture Academy

Viljandi Culture Academy develops creative entrepreneurship in an international incubation programme. By combining cultural heritage, research and business, the programme participants are looking for innovative applications of heritage to support its vitality. The programme’s areas of activity range from climate change and sustainable energy to healthy lifestyles and food.

August – “NOBALwheat – breeding toolbox for sustainable food system of the Nordic- Baltic region”

In the research project of Hannes Kollist, Professor of Molecular Plant Biology, and Ebe Merilo, Associate Professor of Plant Biology of the Institute of Technology, “NOBALwheat – breeding toolbox for sustainable food system of the Nordic-Baltic region”, research groups measure the gas-exchange characteristics in wheat to identify their potential for breeding climate-resilient wheat varieties.

The aim of the project is to breed climate-resilient wheat varieties to ensure food security and agricultural stability in the Nordic and Baltic countries. By means of phenotyping and genotyping technologies, the researchers aim to find high-yielding varieties that could withstand climate change, and that can be grown resource-efficiently.

September – UT Move Lab's initiative "Schools in Motion"

The UT Move Lab looks for evidence-based approaches to help make the school day more physically active. Their initiative "Schools in Motion" supports schools to make every day an active one for pupils and teachers alike. Estonian children and young people still spend too much time in front of screens: only 21% of children spend less than two hours a day looking at a screen in their free time. Nor have they started to play outdoors more or become more active on their way to school. The University of Tartu Move Lab is working to make physical activity an integral part of the school day in more and more Estonian schools.

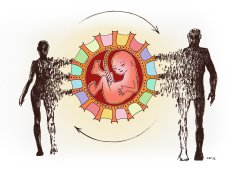

October – “Exploiting genomic lottery to understand causality between personality traits, cognition, and health”

The research by Uku Vainik, Associate Professor of Behavioural Genetics at the Institute of Psychology, “Exploiting genomic lottery to understand causality between personality traits, cognition, and health”, aims to collect the behavioural traits of 220,000 participants of the Estonian Biobank. These causal associations are largely unknown, as randomised trials are expensive and often ethically impossible. In this project, the researcher proposes using a genomic causal inference method – Mendelian randomisation. This method uses the genetic lottery – the natural randomisation of genetic markers that either enhance or reduce certain behavioural traits in people.

November – “Integrating big health and social data to understand and reduce health inequalities”

The research by Taavi Tillmann, Associate Professor of Public Health at the Institute of Family Medicine and Public Health, “Integrating big health and social data to understand and reduce health inequalities”, aims to reduce health inequalities by creating a new, fully representative health database for future studies. To this end, Tillmann links the health records of 660,000 residents (aged 40–74) with the health information system and four national databases on education, ethnicity, unemployment, occupation, municipality, marital status and social benefits.

December – “Novel high-performance polymers from lignocellulosic feedstock”

The research by Lauri Vares, Associate Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Institute of Technology, “Novel high-performance polymers from lignocellulosic feedstock”, helps reduce industry dependence on fossil resources. Bioplastics can be produced from wood sugars derived from wood residues. On the one hand, this would help reduce the packaging industry’s dependence on oil. On the other hand, it would help produce higher added-value products from wood waste, which is currently used mainly for heating, and to capture for a longer time the CO2 that is otherwise emitted with flue gases into the atmosphere. The development of such production technology is essential for stimulating a waste-reducing circular economy.

In the course of the project, the environmental impact of the novel technology will be analysed and compared with the environmental impact of the existing fossil-based plastics.