Researchers found that around a third of genes for allergic and autoimmune diseases were important for human adaptation

Autoimmune and allergic diseases are on the rise. It is still not clear why our immune system starts destroying our tissues and causes these chronic diseases. Recent discoveries clarified some of the elements of this self-destruction, but autoimmunity remains an unsolved puzzle. A new study published found that genetic factors for a range of autoimmune and allergic disorders were important for human adaptation. So, the intriguing question is whether beneficial adaptations, presumably to pathogens, demonstrate their flip coin side and how this can help us better understand pathology and think about treatment?

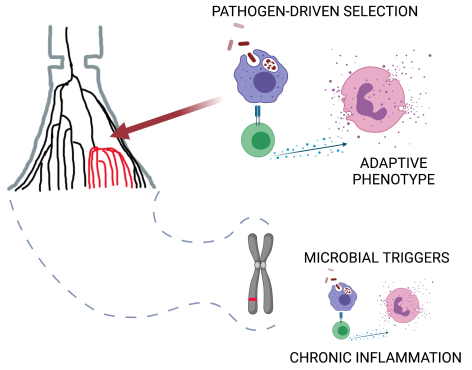

A group of geneticists from the University of Tartu used Estonian Biobank sequence dataset to study hundreds of genomic regions associated with 21 autoimmune diseases. Among them are Type 1 diabetes, Psoriasis, Multiple Sclerosis, and others. They applied bioinformatic tools to reconstruct how these disease-associated genomic regions evolved in the past. They showed that almost a third of disease genes were under natural selection. „Assuming that pathogens imposed natural selection, it means that immune mechanisms important to combat pathogens are now damaging our tissues. Hence, we hypothesize that the same stimuli – microbes – can be provoking these adaptive mechanism,” said Dr Bayazit Yunusbayev, the lead author of this study.

Trying to detect small effects experimentally can be challenging since small effects can be easily obscured by the genetic background noise. Therefore, one has to somehow prioritise high impact genetic loci. Our findings can be used to prioritise genetic loci for experimenting. Here, our assumption is that natural selection picked immune gene variants that had tangible and, perhaps strong, effect at organismal level. This is largely untested idea, though.

Genetics of the autoimmune disease involves dozens and hundreds of genetic loci, but their individual effects on disease risk can be small, Dr Yunusbayev continiued. „Trying to detect small effects experimentally can be challenging since small effects can be easily obscured by the genetic background noise. Therefore, one has to somehow prioritise high impact genetic loci. Our findings can be used to prioritise genetic loci for experimenting. Here, our assumption is that natural selection picked immune gene variants that had tangible and, perhaps strong, effect at organismal level. This is largely untested idea, though,” he said.

Authors explained that when probing gene function, one must know the relevant tissue and cell type – autoimmune diseases usually involve multiple tissues and cell types. „Finding the right cell type and physiological context is challenging. For the subset of disease genetic variants under selection, we tried to predict their cell type, where these genes are being expressed. This can be a valuable resource for other researchers to design experiments” added Dr Yunusbayev.

Finally, immune cells and genes are designed to respond to environmental cues and function in specific physiological contexts. Infectious agents have long been proposed as autoimmunity triggers. Evolutionary perspective seems to favour this view since genes were optimised to interact with microbial exposure. Researchers emphasize that in the case of autoimmunity, we are talking about not frank pathogens but microbes living with us – commensals and symbionts. „They can be the missing piece of the autoimmunity puzzle. To understand the function of these disease genes, we should model their function using microbial triggers. It means that when we think about new treatment strategies in the future, we should first understand our relationship with microbes and think about targeting microbes living with us. Broadly speaking, to heal, we should understand how our genes respond to the microbial world, the world that we humans dramatically disturbed over the past 100 years,” said Dr Yunusbayev.